“It’s like architecture in your head”

After a self-imposed exile, neo-classical boy wonder Nils Frahm is back with a long-awaited new album, a revamped live show and his own studio, which he reckons sounds better than Abbey Road. Tom Pinnock discovers what the pianist and composer has been up to, and hears why making his new LP is like playing Jenga: “This album was the biggest confusion I’ve ever caused myself…”

“I’m having nightmares about it,” laughs Nils Frahm, discussing his upcoming live dates, his first since 2015. “I had one dream where I set up everything, the show was starting, and I came onstage and all the gear was gone – they had to take everything down because the support act needed more space… I was like, ‘But… but… but…’ and then I woke up! But it’s going to be something, for sure.”

Once you couldn’t keep him from the stage, but Frahm has now spent three years away from live performances, instead building his own studio in a former East German broadcasting facility, where he’s recorded an excellent new album, All Melody, and reworked his live setup from the ground up.

“I stopped touring because whatever I was doing in that moment was not really what is possible,” he explains. “I didn’t like the last shows I was doing in 2015 – I needed to reorganise everything.”

Throughout 2018, the 35-year-old is returning to live work with what he admits is “the most complicated setup I’ve ever brought on tour”, including three Roland Juno synthesizers, a piano, a Fender Rhodes, three drum machines, a pump organ, four Roland Space Echos and a Mellotron – a set of vintage equipment that needs constant care on the road.

“It’s a nightmare to travel with,” Frahm explains, “but that’s also exactly why I love it so much, because I feel like only somebody crazy would bring it on tour, only somebody who’s lost his mind! I am selling out shows, so I have more means. I would feel horrible to just buy a beautiful house and take a laptop on tour, so I try to re-invest as much as I can in the music and the art.”

Since he emerged as one of the prime movers of the blossoming neo-classical scene a decade ago, Frahm has continually moved forwards with his recording work: notable LPs include 2011’s Felt, recorded with his piano muted and close-mic’ed so he could play in his home at night, and the diverse, sprawling Spaces from 2013.

His new record, All Melody, however, is his most progressive and dynamic album yet. A 74-minute epic, it moves between piano, electronics and choral arrangements, with a 20-minute centrepiece of buzzing, pulsing, kosmische electronica in the form of the title track and #2. Frahm has touched a little on some of these soundscapes before, but the remarkable thing about All Melody is just how well the record flows, its disparate moods woven into an undulating whole; something of a musical journey, if you will.

“I really like making mixtapes,” Frahm explains, “with the Late Night Tales mix and my Christmas mixes – ‘How do I get out of a Miles Davis song and make it into a Beethoven piece without it feeling weird?’ I knew that if I wanted to make a Nils Frahm record where those two pieces were included [‘All Melody’ and ‘#2’], then the whole record would need to be a little bit less piano-focused. I had the peak already, but I needed to invent the path towards that peak.”

Frahm began by attempting to meld the piano with electronics, but found the results were often “cheesy… like chill-out music or spa music.” That’s when he stumbled upon the strategy of keeping his different ideas separate. “You might eat a potato here, then a piece of meat here, something spicy here…”

So alongside the motorik electronica of “All Melody” come the ambient grooves of A Place, complete with the subtlest of choirs (inspired by South American Christmas music, says Frahm), the gorgeous, nocturnal solo piano of Forever Changeless (the title referencing one of Frahm’s favourite Keith Jarrett LPs, not Love’s psych opus), the Edgar Froese-esque arpeggios of Kaleidoscope and the funereal harmonium elegy of Harm Hymn. It’s moody, beautiful and sounds effortless. Not so, according to its creator.

“To be honest,” he admits, “the whole album was the biggest confusion I’ve ever caused myself. I had basically no idea what would really happen, so it was a bit of a difficult one. For my own sake, and my own curiosity, I needed to do something which was a little bit further away from my other work. It’s always important to keep the whole catalogue of your work in mind when you record, but it does make it harder to make a new record – it’s a bit like the game Jenga, where you pull a stick from the bottom and put it on top!”

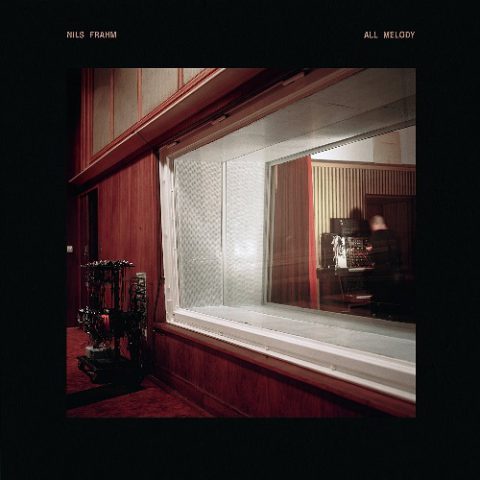

To create All Melody, Nils Frahm built his own dream studio, Saal 3, in the Funkhaus, the old East German complex from where the DDR would transmit radio, record artists and develop new broadcasting technology – until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, of course, after which it remained largely disused for decades.

“The rooms are some of the best-sounding ever built,” enthuses Frahm, “comparable to Abbey Road. You could argue that it’s even better than Abbey Road in many respects.”

As well as practicing with his new live setup, placed in the middle of his 600-square-foot live room, the pianist and his team have built much of their own equipment, including a mixing desk which has been two years in the making. “We try to basically go back in time,” he explains, “and work with equipment that we love so much – stuff from the ’50s and ’60s was usually built much better than crap from today. We reconnected the echo chamber, and made it work again. We’re trying to learn from all that vast knowledge of pure engineering from the past.”

That echo chamber appears on every track on All Melody, but Frahm often teams it with digital reverb to shape unreal spaces that fool the listener’s ear. “I like when it doesn’t sound so artificial, but it also doesn’t sound like a complete realistic acoustic space. It’s like architecture in your head – it drives the imagination when you build reverbs that are not real.”

Frahm is soon to be leaving the comforting wonderland of Saal 3, however, to mount his extensive, no-expense-spared tour, which promises his most spectacular, organic performances yet. He calls at the UK in late February, on a jaunt that includes multiple nights at London’s Barbican.

“Whatever I do, I try to find a different path from everybody else. Usually people use Ableton Live to sequence onstage, but I’m using Cubase. I just create a certain pattern and then I have to do the song manually by starting different instruments and changing chords or filters – I try to have as much in my hands as possible, but it’s also a way to make it feel different every time, so no concert is the same. That is really important for me, that I have a journey with the material.”

Nightmares aside, though, he’s looking forward to returning to the stage in a big way.

“It feels like I only just started understanding what I’m doing there,” he says, “and I needed two or three years to really focus on all the details and really practice and practice. And now I feel really happy I did.”

Tom Pinnock