in-store offers

10 of the best

KItchen Sink Realism

Explore our promotion celebrating the finest of Kitchen Sink Realism, featuring generous price markdowns on DVD and Blu-ray!

In the wake of post-war Britain, an artistic revolution emerged, giving rise to what would be termed Kitchen Sink Realism. This movement’s cinematic facet became renowned as Kitchen Sink Cinema or the British New Wave. Emboldened by a fervent desire to mirror the stark realities of working-class existence, filmmakers like Tony Richardson dared to peel back the layers of societal veneer. Their canvases were not embellished with the gloss of Hollywood glamour, but rather etched with the gritty truths of everyday life—poverty, unemployment, and the suffocating confines of societal norms. Grounded in a naturalistic aesthetic, the films pulsated with the rhythms of authenticity, employing real locations and unvarnished dialogue. Though the British New Wave ebbed relatively swiftly, its resonance endured, challenging the status quo and inspiring future generations of filmmakers to confront the unvarnished truths of class and society. To celebrate our current promotion on Kitchen Sink Cinema, let’s go through 10 of our favourites from the genre…

A Taste of Honey (1961)

Shelagh Delaney’s play A Taste of Honey had already played in the West End and on Broadway when Tony Richardson made his film adaptation, which was shot on location in Salford and Blackpool. Rita Tushingham made her indelible screen debut as Jo, a young girl who falls pregnant after leaving home and her floozie of a mother – a revelatory performance by Dora Bryan. Jo befriends Geoff, a gentle, kind-hearted gay man, and they move in together like two children playing house, for a while finding an innocent but fragile happiness. Richardson, always skilled with actors, draws fine performances from his entire cast, and A Taste of Honey remains an outstanding example of the British New Wave, shot by its star cinematographer Walter Lassally.

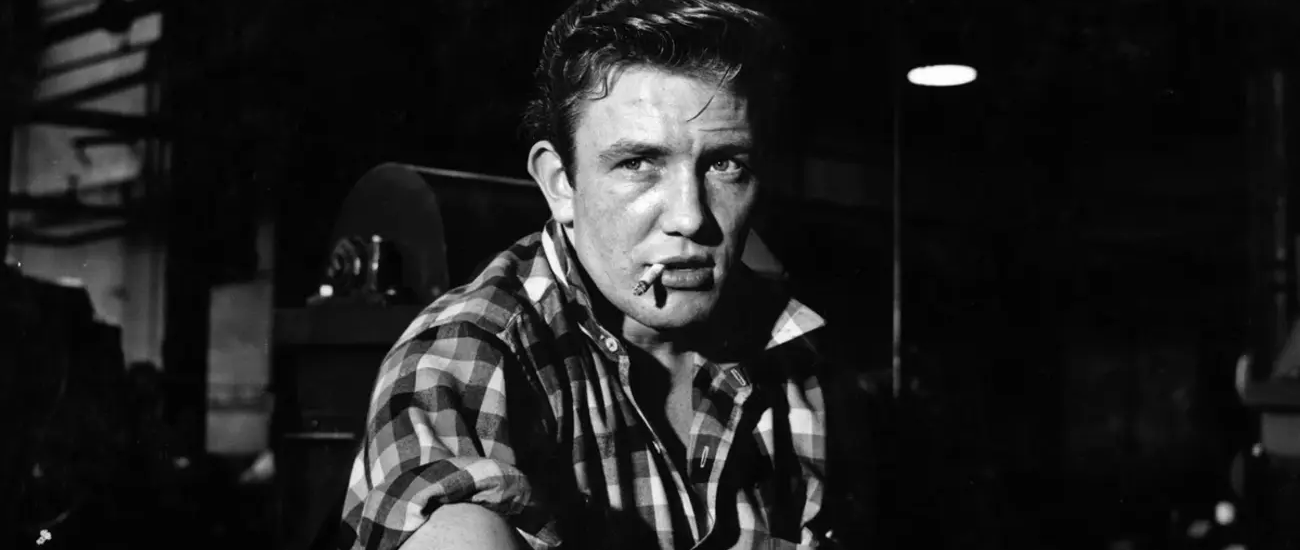

Look Back in Anger (1959)

Captured through the lens of the esteemed Oswald Morris, the film commences with a mesmerizing scene unfolding in a jazz club. Trumpeter Jimmy Porter (Burton), a disillusioned, educated individual, wages a relentless battle against the Establishment, laboring by day at a sweet stall in the market. His downtrodden, middle-class wife bears the brunt of his tirades, yet when he seeks solace in an affair with her best friend, it unleashes untold misery upon all who know him. Tony Richardson’s inaugural feature serves as the quintessence of the kitchen-sink drama, birthing a new wave of British social protest films and heralding the advent of the liberated swinging sixties. Apt for contemporary times and retaining its disquieting allure, this narrative remains as uncomfortably compelling as ever.

Room at the top (1959)

In post-war industrial Yorkshire, social climber Joe Lampton (Laurence Harvey) endeavors to win the boss’s daughter’s affections as he ambitiously strives for professional success. Yet, his humble working-class origins become formidable barriers impeding his ascent, leading him to find solace in an illicit affair with Alice (Simone Signoret), a woman trapped in an unhappy marriage—a dalliance fraught with dire consequences. Directed by Jack Clayton, the film offers a nuanced exploration of sexuality and class dynamics, unfolding against the backdrop of post-war Britain. Recognised with two Academy Awards, including a well-deserved Best Actress accolade for Signoret’s captivating portrayal and the prestigious Best Adapted Screenplay honor, the film crystallises the era’s societal tensions and personal dilemmas with unflinching honesty, cementing its place as an enduring classic in the annals of cinematic history.

The L-Shaped Room (1962)

The L-Shaped Room attracted international acclaim for its star Leslie Caron who was awarded both a Golden Globe and a BAFTA for her portrayal of Jane. A young French woman pregnant with an illegitimate child, Jane arrives at a dingy Notting Hill lodgings to have her child in secret, but finds love and friendship among the assortment of outsiders living in the boarding house – all brought to life by Forbes’ sensitive ear for dialogue. In addition to the especially moving Cicely Courtneidge as a faded music hall star growing old alone and Pat Phoenix’s portrayal of a tart with a heart, Toby, a struggling young writer on the first floor who Jane falls for and Johnny, a black jazzman rejected for more than his colour. Ever since Hitchcock’s The Lodger, the London boarding house has proved an evocative location through which to explore the underside of British society and The L-Shaped Room’s sensitive study of social morals at the dawning of the Sixties sexual revolution, is no exception.

The Entertainer (1960)

Adapted from a stage play by John Osborne and directed by Tony Richardson, The Entertainer is a brilliantly caustic portrait of ageing music-hall veteran Archie Rice. Laurence Olivier delivers one of his finest screen performances, with his portrayal of a man coming undone at the seams and revealing the emptiness inside. Set against the Suez crisis, the identity of post-war Britain is transposed to the theatre stage, as a fatigued generation makes way for an energised youth, embodied by a supporting cast on the cusp of stardom – including Alan Bates, Joan Plowright and Albert Finney. The film went on to garner Olivier yet another Oscar nomination.

The Loneliness of the long distance runner (1962)

Colin (Tom Courtenay) is a defiant teenager who rebels against the system, refusing to follow his dying father into a factory job, railing against the capitalist bosses and preferring to make a living from petty thieving. Sent to borstal, Colin discovers his talent for cross-country running. The borstal governor (Michael Redgrave) offers him the chance to redeem himself in a race against a local public school, and tensions build as the day approaches. Following the huge success of Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Alan Sillitoe here adapted another of his own novels for the screen. Newcomer Tom Courtenay is totally compelling as the sullen, disillusioned delinquent in this British New Wave classic, a passionate, explosive tale of rebellion.

Poor Cow (1967)

Ken Loach’s classic 1967 feature debut, Poor Cow, followed on from his hard-hitting work in television, Poor Cow brought Loach’s unique, uncompromising style to a big screen audience and helped kick start a new movement in social realist filmmaking. In a gritty 1960s London, Joy (Carol White, Cathy Come Home) is a young mother who is forced to fend for herself when her brutal and uncaring husband, Tom (John Bindon, Barry Lyndon, Get Carter), is put in jail. The film unfolds as Joy navigates the landscape of 1960s London, grasping at the slender threads of happiness amidst the bleakness of her circumstances. Encountering Tom’s seemingly compassionate associate Dave (portrayed by the talented Terence Stamp, known for his roles in Far from the Madding Crowd and The Limey, Joy finds herself drawn into a complex web of relationships while single-handedly raising her son amidst the squalor of her environment.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960)

Director Karel Reisz’s adaptation of Alan Sillitoe’s novel about a hard-living factory worker and the married woman he seduces. Arthur Seaton (Albert Finney) is a young man filled with a rage perhaps even he doesn’t fully understand. Working in the tough environment of a Nottingham factory, he compensates for the drudgery and discipline of his weekday life with weekends spent drinking and womanising. His affair with a fellow factory worker’s wife, Brenda (Rachel Roberts), seems especially ill-advised – particularly when Brenda informs him that she is pregnant with his child. With abortion illegal at the time, Arthur and Brenda face a difficult dilemma. Will Arthur face up to the kind of domestic responsibilities he openly scorns in his own parents, or run harder than ever?

The Family Way (1966)

Based on Bill Naughton’s warm-hearted play All In Good Time, featuring an original soundtrack by Paul McCartney (with George Martin), and directed by the Boulting brothers – Roy and John – The Family Way is a tender and funny exploration of the emotional impact of the Sixties sexual revolution focusing on two sensitive youngsters whose failure to consummate their marriage threatens to derail their life together before it has even begun. Jenny and Arthur’s wedding night is disrupted by Arthur’s father and rowdy guests, leading to a series of unfortunate events including a collapsed bed and stolen honeymoon funds. Unable to find privacy or financial stability, their unconsummated marriage strains under the pressure of their crowded living situation, sparking gossip and exacerbating their relationship woes.